Sarah Stetner is proudly raising two young techies. Her sons Gabriel, 3, and Isaiah, 6, are media mavens who know their way around an iPad — and almost every other device on the market. “Leapster, iPad, Wii, Xbox, computer, they do it all,” she says. The Stetners set media limits for ‘”non-educational” media and TV shows but not for learning-oriented video games and devices. “Those, they can play all they like,” says Stetner.

Just how educational those devices are is the subject of debate. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends no screen time for children younger than 2 and limits for older children, based on the claim that so-called “educational” video games and TV shows have no proven learning benefits.

But the issue is actually more complex than that, according to Eric Kirkendall, M.D., M.B.I., F.A.A.P., from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. “Technology’s a fascinating thing,” he says, “and it’s hard to keep up with the changes.”

Learning Debate

As families snap up smartphones, tablets and educational techno toys, the debate over their educational value is heating up. So is the question on how realistic is it to expect to keep tots away from all screens, whether TV or computer. Many modern kids live in homes where media devices outnumber people. Common Sense Media reports 40 percent of 2- to 4-year-olds use smartphones, tablet computers or similar devices. Nearly half (44 percent) of preschoolers have a TV in their bedroom. Younger kids see plenty of screens, too: the AAP reports that 90 percent of children younger than 2 use some form of electronic media daily.

That information alone doesn’t necessarily take on significance until you look at the content kids are watching and the amount of time they spend watching it, according to Kirkendall. He points to a recent study of older kids that found those who spent an hour or less per day playing positive, educational video games showed a greater ability to concentrate and express empathy for others. The effect was rendered neutral for kids who spent one to three hours on those same games, but for those who spent more than three hours playing the games showed a decreased ability to pay attention and show empathy.

One thing researchers and the AAP agree on: a child’s potential for technology-aided learning depends largely on age. For babies and toddlers, the AAP says educational programming and media devices don’t boost learning. That’s because most babies and toddlers lack the critical contextual knowledge that enables them to learn from a TV program. “DVDs don’t actually fit with how kids really learn language,” says Kirkendall. For example, when a child and parent are playing with a ball, the parent can say the word “ball” and give his child the actual object to see and touch. Characters on TV can’t introduce an object in the same direct way. However, Kirkendall does point out that there are a few TV shows out there like Blue’s Clues that tell simple stories and often address the audience directly, which mimics human interaction. (So don’t stress out if you find yourself resorting to Blue in order to distract your kid for a few minutes!)

For preschoolers, the hubbub about media overexposure isn’t because most media is harmful in and of itself, notes Kirkendall. Instead, the concern centers on what kids miss out on when they’re parked in front of a screen, especially when it comes to one-on-one time reading and interacting with someone else. “Human interaction is always going to trump screen time,” he says.

Screen Awareness

Video games and other educational devices are not necessarily devoid of benefits, but it really comes down to using well-designed products in the right circumstances with the right adults. They can even be confidence builders for older kids playing and succeeding at a game, says Kirkendall. He advises parents to simply keep an eye on the content and the amount of time your kid spends with them.

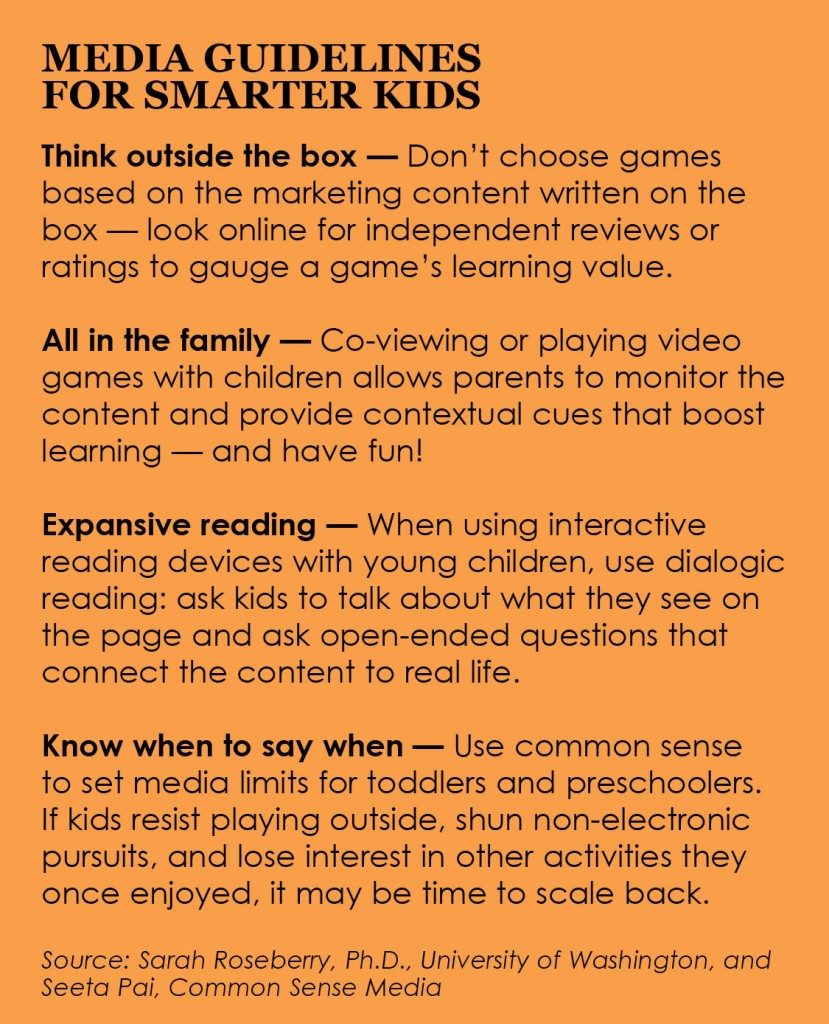

That means media that takes the place of parental interaction — or serves as a babysitter for busy parents — won’t have much learning value, no matter how great the content. Co-viewing and playing video games together allows parents to connect what’s happening on-screen to real life, providing the vital context that fuels learning. Young kids need parents to help bridge the gap between the screen and real life.

Definitive answers on the educational value of media use for young kids may be years away. In the meantime, Common Sense Media offers Learning Ratings, a program that offers “best for learning” ratings and reviews for video games and apps. The ratings (currently in BETA testing) are designed to help parents navigate the confusing world of kids’ media and help kids make better media choices. Or, as Kirkendall advises, when in doubt, talk to your pediatrician and work with him or her on what’s OK for kids to see and use as they grow.

For the Stetners, though, the lesson is clear: electronics can teach, but they can’t replace life experience. From learning basics like letters and numbers to life skills like coordination and sportsmanship, Stetner says video games and computers have made her kids smarter. But when the weather’s nice, she sends the boys outside to race, wrestle and tumble in real-life dirt and grass — an experience no computer game could ever replicate.